Historical and projected changes in climate predictability

The “potential” predictability of the climate system (i.e., a prediction limit intrinsic to the chaotic nature of climate) has varied throughout the historical record, primarily due to natural decadal variability. In Amaya et al. (2025), the authors use statistical methods applied to five coupled model large ensembles to diagnose whether and how potential predictability is projected to change in the future as a distinct response to anthropogenic climate change. Specifically, they apply the perfect model-analog framework to estimate the seasonal predictability limits of global surface temperature, precipitation, and upper atmospheric circulation from 1920-2100.

In the traditional model-analog framework, the observed climate state is compared to a large library of model data to find similar climate states, with the subsequent evolution of the model then treated as a forecast of reality. The perfect model-analog technique leverages these same methods but with the alternative goal of forecasting the climate simulations itself rather than the real world. This is accomplished by treating a portion of a climate model as the “truth” while finding similar analog climate states from a different, independent portion of the same model. The resulting forecast is “perfect” in that it has no biases or errors relative to the “observations” it is compared against. Therefore, its prediction skill is “perfect” and represents that model’s estimate of the potential predictability of the climate system. By generating tens of thousands of perfect model forecasts for different time periods in the models, the authors are able to explore how potential predictability in the climate system changes in the past, present, and future.

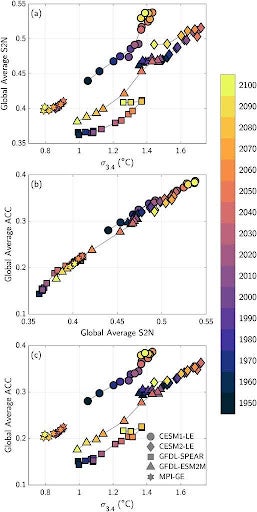

The authors find that historical and projected changes to the amplitude of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) generate global-scale shifts in climate predictability via ENSO-driven changes in the signal-to-noise ratio of seasonal forecasts. This relationship suggests that potential predictability changes across much of the globe in the coming decades could be linked to anthropogenic climate change of ENSO. However, since current models substantially disagree on the sign and intensity of projected ENSO change, the trajectory of future global predictability changes cannot yet be determined. This problem is demonstrated by widely varying predictability changes seen across the five large ensembles, with models exhibiting a robust increase, robust decrease, or no significant change in predictability, depending upon their respective projected ENSO amplitude trends. Still, the results of Amaya et al. (2025) demonstrate that if ENSO variability were to decrease in the future, as suggested by several recent studies (Wengel et al. 2021; Callahan et al. 2021; Peng et al. 2024), then historical forecast skill relationships that depend on ENSO and its teleconnections (such as El Niño typically increasing the likelihood of rainfall in the American Southwest) may become less reliable as these regions become less predictable.

Figure 1. (a) Global average sea surface temperature anomaly (SSTA) forecast signal-to-noise (S2N) at 12-month lead (y axis) vs DJF averaged Niño-3.4 standard deviation (x axis) in different coupled model large ensembles (different shapes) and different 30-yr periods (shading). (b) As in (a), but for global average SSTA forecast skill as measured by anomaly correlation coefficient (ACC) vs global average S2N ratio. (c) As in (a), but for global average ACC vs Niño-3.4 standard deviation. Shading of each shape indicates the 30-yr window over which the forecast skill, S2N ratio, and Niño-3.4 standard deviation are calculated, with the year indicating the end of the window. For example, the shading for 1950 corresponds to 1921–50.

Linking Projected Changes in Seasonal Climate Predictability and ENSO Amplitude (Journal of Climate)

Topics

- ENSO

- Modeling

- Climate Change