Record-high Beaufort Sea freshwater content could alter local and global ocean circulations

The Beaufort Sea, which is the largest Arctic Ocean freshwater reservoir, increased its freshwater content by 40% over the past two decades. How and where this water will flow into the Atlantic Ocean is important for local and global ocean conditions. A new study by Zhang and colleagues in Nature Communications shows that water from the Beaufort Sea mostly traveled through the Canadian Archipelago channels to reach the western shelves of the Labrador Sea, rather than through the much wider Fram Strait, which is traditionally believed to be the major pathway for Arctic water to flow into the North Atlantic.

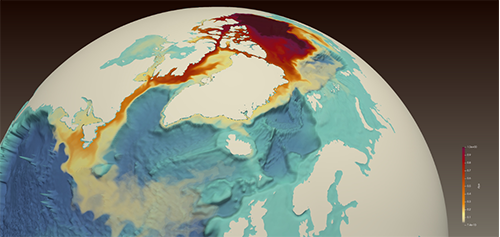

Dye tracer released from the Beaufort Gyre region of the western Artic Ocean indicates freshwater transport through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago into the western Labrador Sea, causing freshening there. Image credit: Francesca Samsel and Greg Abram (University of Texas at Austin).

Using a global ocean-sea-ice model imbedded with passive tracers, Zhang and colleagues simulated ocean circulation and tracked the Beaufort Sea freshwater’s spread during a historical release episode from 1983 to 1995. They show that the Canadian Archipelago is actually an effective conduit that connects the Beaufort Sea and the high-latitude North Atlantic, which had long been overlooked.

Their findings have implications for the Labrador Sea marine environment, since Arctic water tends to be fresher but also rich in nutrients. This identified pathway also potentially affects larger oceanic currents over longer time scales, namely the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)—in which colder, heavier water sinks in the North Atlantic and comes back along the surface as the Gulf Stream. Fresher, lighter water entering the Labrador Sea could slow the overturning circulation.

The volume of freshwater currently in the Beaufort Sea is about twice the size of the case studied in Zhang et al., at more than 23,300 cubic kilometers. If released into the North Atlantic, sooner or later, this extra volume of freshwater could be even more impactful. The strength of the AMOC has recently been found to be at its weakest point in the past 1,000 years. If freshening continues over the region where source water forms, the AMOC may get further slowed down. When and how fast the Beaufort Sea is going to release this extra freshwater is unknown, but some early signs indicate such a process may have already started.

Labrador Sea freshening linked to Beaufort Gyre freshwater release (Nature Communications)

Topics

- Modeling

- Atlantic Ocean

- Arctic

- AMOC