Small island nations face drier conditions by mid-century

Future changes in freshwater availability are a major concern in the context of climate change regardless of whether one lives in the middle of an enormous continent or on a tiny island. Changes in aridity—the ratio between evaporation and precipitation—are expected in many regions as a result of climate change. Many studies including the IPCC reports provide future predictions of evaporation, soil moisture, and aridity, but those maps are simply blank over the ocean. Islands smaller than the spatial resolution used in global climate models (GCMs)—including French Polynesia, the Marshall Islands, and the Lesser Antilles—are difficult to assess because GCMs can only provide estimates of precipitation there, not potential evapotranspiration. Insufficient resolution, therefore, precludes such knowledge for approximately 18 million people living on small islands scattered across the world ocean.

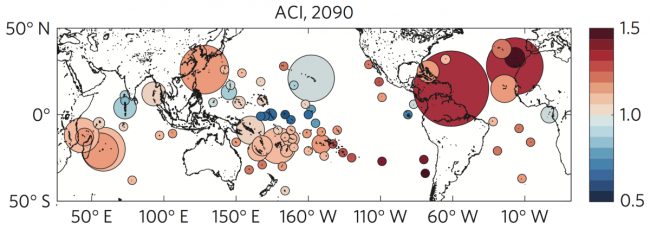

To overcome this problem, Karnauskas et al. adapted an engineering method for estimating the potential evapotranspiration to GCM output, enabling them to calculate an aridity change index (ACI) for 80 globally distributed island groups. What they found is that although about half of the island groups are projected to experience increased rainfall—predominantly in the deep tropics—overall changes to island freshwater balance will shift towards greater aridity for over 73% of the island groups (16 million people) by mid-century.

It’s often said that climate models weren’t built to tell you what to expect in your neighborhood, but for some small island nations, the neighborhood is what matters. Future freshwater stress has important implications for vulnerable island populations, who must rely on climate adaptation scenarios for agricultural practices and seasonal water management. Furthermore, most of the small island nations that are projected to experience future dryness do not emit greenhouse gases at the levels that continental nations do. For some places, like French Polynesia, increased dryness could compound climate-related threats such as sea level rise. For others that perhaps were not as concerned about sea level rise, this could be a new issue to start thinking about.

Future freshwater stress for island populations (Nature Climate Change)

1University of Colorado Boulder

2Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

3University of Arizona

Topics

- Modeling

- Climate Change

- Ecosystem Impacts

- Extreme Events