Research Highlights

We aim to feature the latest research results from US scientists whose published paper features work that is sponsored by one or more sponsoring agency programs of US CLIVAR (NASA, NOAA, NSF, DOE, ONR). Check out the collection of research highlights below and sort by topic on the right. Interested in submitting an article for consideration? See our Research Highlight Submission Guidelines page for more information.

New research shows the extent and development of 'the Blob' using satellite surface temperature data to reveal warm temperature anomalies appearing as early as March 2014 in the central and southern California coast, and eventually extending to the entire West Coast and dissipating in August 2016.

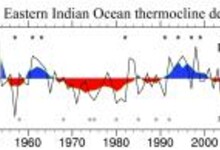

In a new paper from Journal of Climate, researchers show that changes in the Indian Ocean subsurface heat content over the last 50 years can be linked to Pacific Ocean variability associated with the Pacific Decadal Oscillation/Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation.

A recent investigation has shown that in the abyssal southeast Indian Ocean the Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) freshening and warming have changed over the last decade. After a third full repeat of line IO8S in the region, GO-SHIP observations suggest strongly accelerated AABW freshening since 2007.

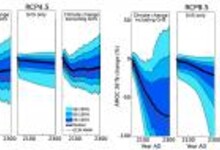

A new study shows that the AMOC is more sensitive to warming, including changes in the atmospheric hydrological cycle, than Greenland Ice Sheet melting. However, Greenland Ice Sheet melt further increases the projected AMOC weakening.

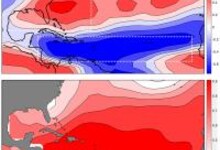

A new study shows that when conditions in the deep tropics are good for hurricane intensification, they are bad along the US coast. This sets up a barrier around the US coast during active hurricane periods that inhibits hurricanes from strengthening and usually causes them to weaken.